Complex Systems and Quantitative Mereology

Have a look at these three rings:

Why are they connected? If you only consider two of the rings and ignore the third, then any pair can be smoothly separated. The triplet is connected and cannot be taken apart, but any description purely in terms of pairwise relationships would miss the fact that the three rings are connected.

While the three rings above—known as the Borromean rings—are especially simple and symmetric, similar links can be created for any number of rings. Here are links of four and six rings, for example, that fall apart if a single ring is removed:

I find this kind of magical. There seems to be a kind of ‘top-down’ causation: the behaviour of individual rings is restricted by the group as a whole, not by any individual.

Making sense of higher-order structure

The rings above are a simple example of a more general phenomenon known as ‘higher-order structure’ or ‘emergence’. These two terms are often used in an imprecise way. Imprecise use of ‘emergence’ does not bother me so much, because it seems to refer to something that is not very precise anyway (similar to ‘complexity’). But I believe that ‘higher-order structure’ can be made much more precise—it certainly sounds pretty mathematical. In fact, I recently wrote a paper about an idea that makes this precise, and that seems to explain many uses of the word ‘higher-order’. In particular, it answers the questions: higher than what? and which order? The paper is called A Mereological Approach to Higher-Order Structure in Complex Systems: from Macro to Micro with Möbius and is publicly available here. In this blog post1, I hope to give a more accessible and less technical overview of the main ideas in the paper.

Mereology

Mereology2 is the study of ‘parts’—specifically the relationship between parts and wholes. My central thesis is that incorporating mereology into scientific and mathematical thinking is a good idea. While a lot has been written about mereology—mostly by philosophers and logicians—it is not widely used as a practical set of ideas in the sciences. I suspect the aforementioned philosophers and logicians would find my approach simplistic, naive, or superficial, but I have found it to be very practical.

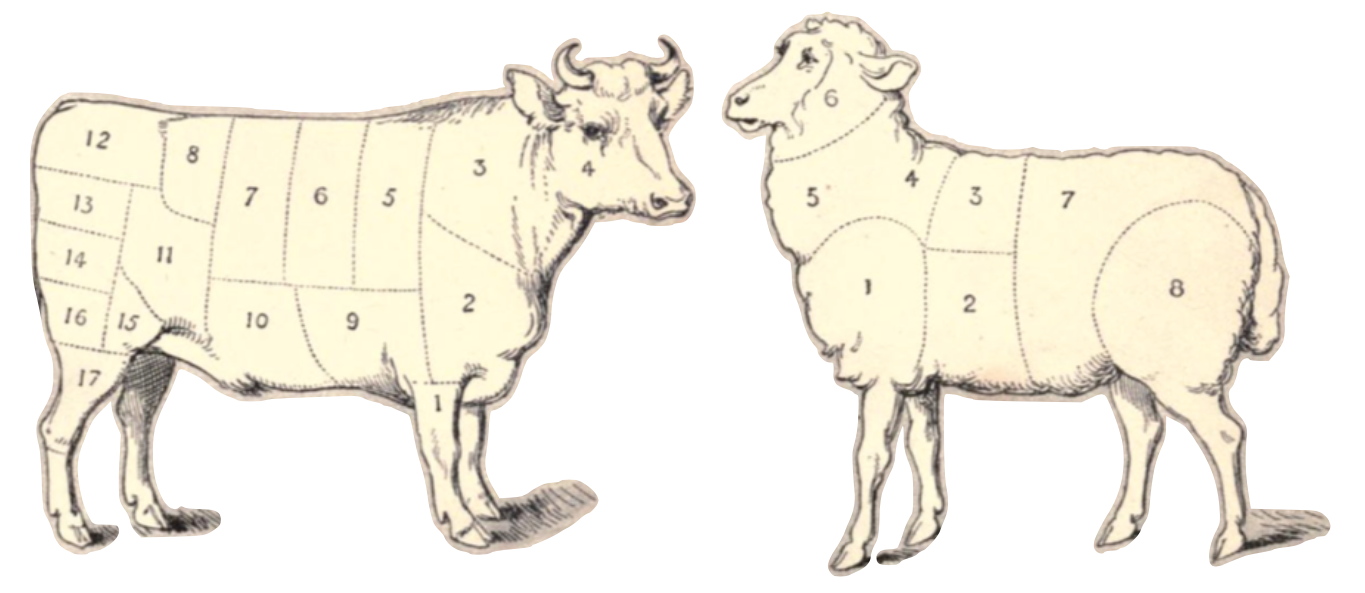

If we want to describe parts and wholes, let’s start with the whole. It is the biggest possible part of itself. The whole can then be divided into smaller parts. One example of this is from the 1886 “Handbook of Practical Cookery” by Matilda Dods:

The parts can be further divided into smaller parts, and so on. It is natural to assume some rules that parts should obey:

- If $a$ is a part of $b$, and $b$ is a part of $c$, then $a$ is also a part of $c$.

- Every part is a part of itself (namely, the ‘trivial’ biggest possible part).

- If $a$ is a part of $b$, then $b$ is not a part of $a$ (unless $a=b$).

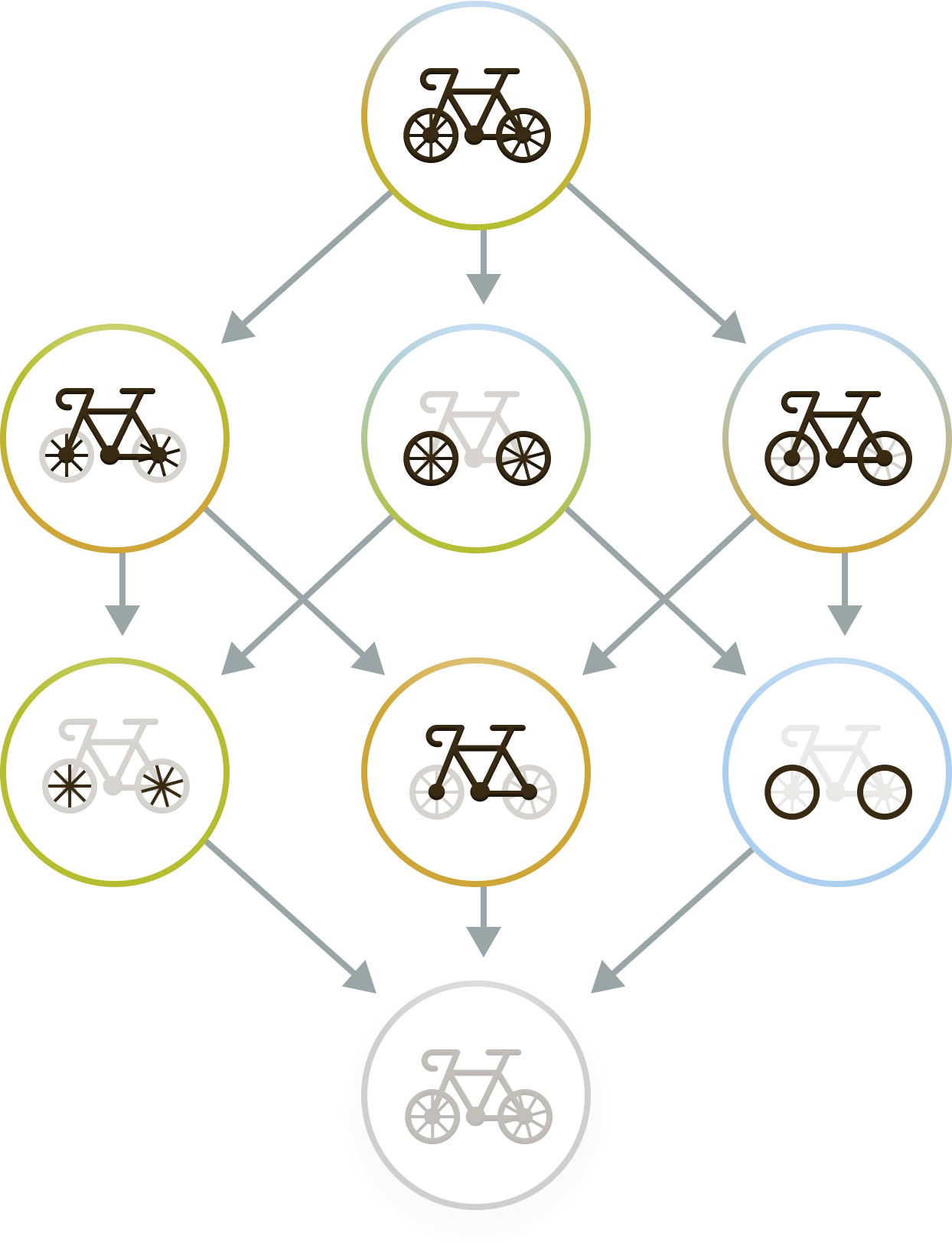

These rules are well-known to mathematicians, who call them transitivity, reflexivity, and antisymmetry. Together, they define what is called a partial order. It gives a way to order a collection of things—in this case, wholes, parts, and parts of parts (and parts of parts of parts, etc.). When a part $a$ is smaller than (or equal to) part $b$, we write $a \leq b$. We say partial order, because not all parts can be put in order! A possible mereology on a bicycle is, for example, the following, where an arrow is drawn from a part $a$ to $b$ if $b$ is a part of $a$:

Clearly, all the components drawn in black are ‘parts’ of the full bicycle, and the ordering reflects that the tires and the spokes are both parts of the wheels. However, the tires are not part of the frame, and vice-versa, so there is no arrow between the two—they are ‘incomparable’.

Now let’s put on a more scientific hat. If we want to describe the mereology of a system, it makes sense to say that there is a unique part that is the biggest, namely the whole system. This is the top of the partial order of parts (for example, the fully assembled bicycle above). In addition, let’s assume that the system is only made up of a finite number of parts (a billion parts is fine, but infinitely many is not). If we call the system $S$, then I propose we call any (finite) partial order that has $S$ at the top a mereology3 on $S$. If we write the set of parts of $S$ as $\mathcal{D}(S)$ and the ordering as $\leq$, then the mereology can be summarised as the pair $(\mathcal{D}(S), \leq)$.

Decomposing Complex Systems

Fundamental to any description of Nature is the choice of parts. I imagine this like the cast of a theatre play: who are the characters that come together to tell the story. If you want to describe how an object behaves, you should decide whether you want to describe it in terms of the atoms, molecules, layers, structural elements, or something else. Once you make this choice, you can start writing down equations that describe how these parts interact. Say you want to predict some property of a system, let’s call it $Q$ for quantity. This could be the temperature of a material, or the height of a person—anything that can be described by a number is allowed here. If $Q$ is some macroscopic quantity that you could measure, then it makes sense to say: $Q(S)$ is the sum of microscopic contributions from all the parts that make up the system $S$. Since I’m imagining $Q$ to be an observable macroscopic quantity, built from microscopic contributions of the parts, I write them as a big $Q$ and little $q$ respectively. Each part can contribute something else, so I write $q(s)$ for the contribution of part $s$. Saying that the quantity $Q$ is the sum of the contributions of the parts can then be written mathematically as:

\[Q(S) = \sum_{s \in S} q(s)\]Where I write $\sum\limits_{s \in S}$ to mean “sum all the parts $s$ that are in $S$”. Now the problem is that this can only really lead to very boring descriptions of the quantity $Q$. If the whole is just the sum of the parts, then your $Q$ is a pretty boring quantity. For example, say we want to describe the height of a person in terms of the genes they have. We could write this as $H(G)$: their height as a function of their genes. If then $H(G) = \sum\limits_{g \in G}h(g)$, then the height of a person is just determined independently by each gene. Biology is much more exciting than that: genes can individually contribute to your height, but they can also interact in complex ways and change each other’s effects. It therefore makes sense to extend our notion of parts to also include combinations of individual genes. For example, we could have contributions of three genes $g_1$, $g_2$, and $g_3$, but also of the pairs $(g_1, g_2)$, $(g_1, g_3)$, and $(g_2, g_3)$—and perhaps even the triplet $(g_1, g_2, g_3)$. Contributions from pairs are very common and usually called interactions. Less commonly considered is an interaction among three elements. Because interactions of more than two elements are less common, they are usually collectively referred to as higher-order interactions4.

Ok let’s therefore assume that in principle, all parts and all possible combinations might contribute to the overall observation of $Q$ (though not all have to contribute—some contributions could be zero in practice). This means that the quantity $Q$ is not just the sum of the contributions of the parts, but also of the contributions of the pairs, triplets, quadruplets, and so on. This can be written as:

\[Q(S) = \sum_{s \in S} q(s) + \sum_{\substack{s_1 \in S\\s_2 \in S}} q(s_1, s_2) + \sum_{\substack{s_1 \in S\\s_2 \in S\\s_3 \in S}} q(s_1, s_2, s_3) + \ldots\]To write this down more efficiently, we define the set of all possible combinations of parts of $S$ as $\mathcal{P}(S)$. Mathematicians call $\mathcal{P}(S)$ the power set of $S$. The quantity $Q$ can then be written as:

\[Q(S) = \sum_{p \in \mathcal{P}(S)} q(p)\]We are now at the point where we can connect this back to mereology. Note that $\mathcal{P}(S)$ has an “order” to it. Let’s say $S = (g_1, g_2, g_3)$, then $\mathcal{P}(S) = (\emptyset, (g_1), (g_2), (g_3), (g_1, g_2), (g_1, g_3), (g_2, g_3), (g_1, g_2, g_3))$. The thing written as $\emptyset$ represents the ‘empty’ set $(~)$, which technically is also a part of $S$—namely the ‘empty part’. Note that some elements of $\mathcal{P}(S)$ can be made from others. For example, $(g_1, g_2)$ can be made from $(g_1)$ by adding $(g_2)$. In this sense, $(g_1)$ is a ‘part’ of $(g_1, g_2)$, and $(g_1, g_2)$ is thus “bigger” than $(g_1)$. This is usually written as $(g_1)\subseteq (g_1, g_2)$. It should not be too hard to convince yourself that $\mathcal{P}(S)$, ordered in this way by $\subseteq$, is a mereology on $S$!

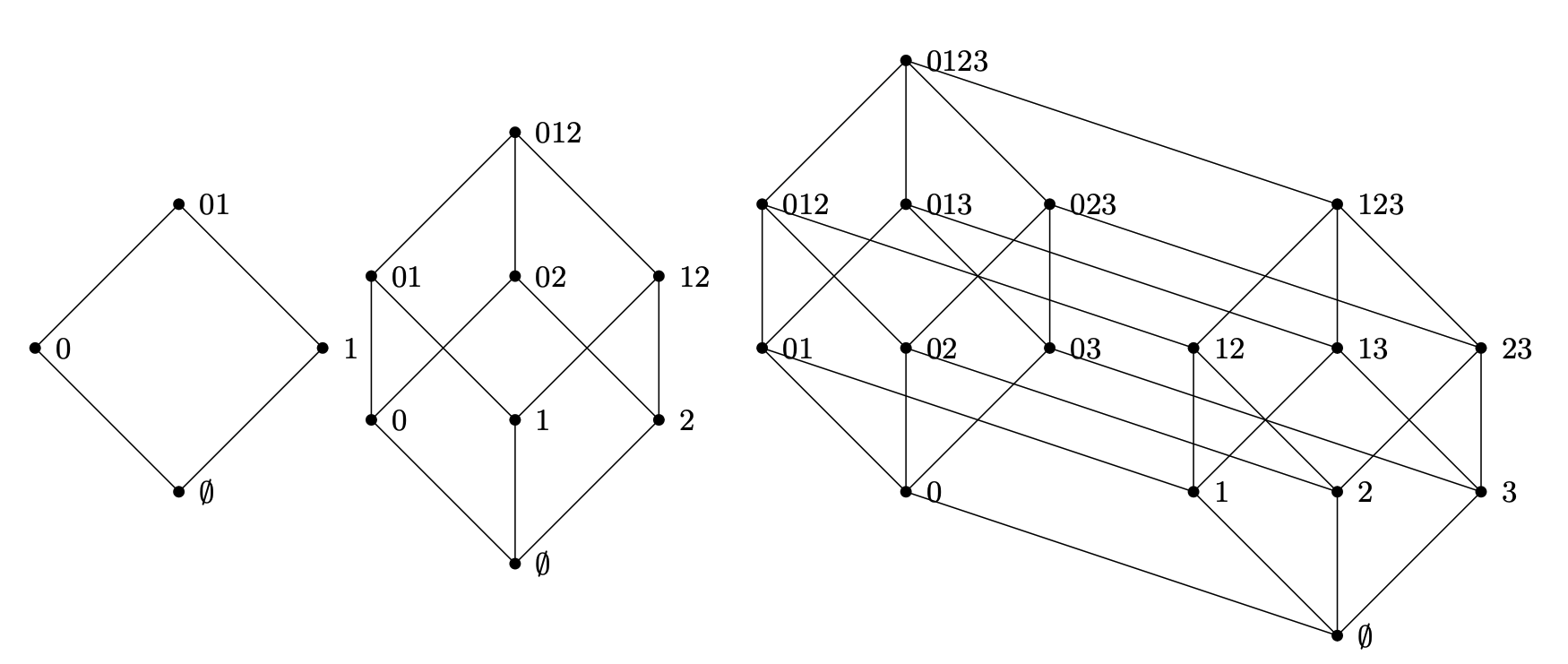

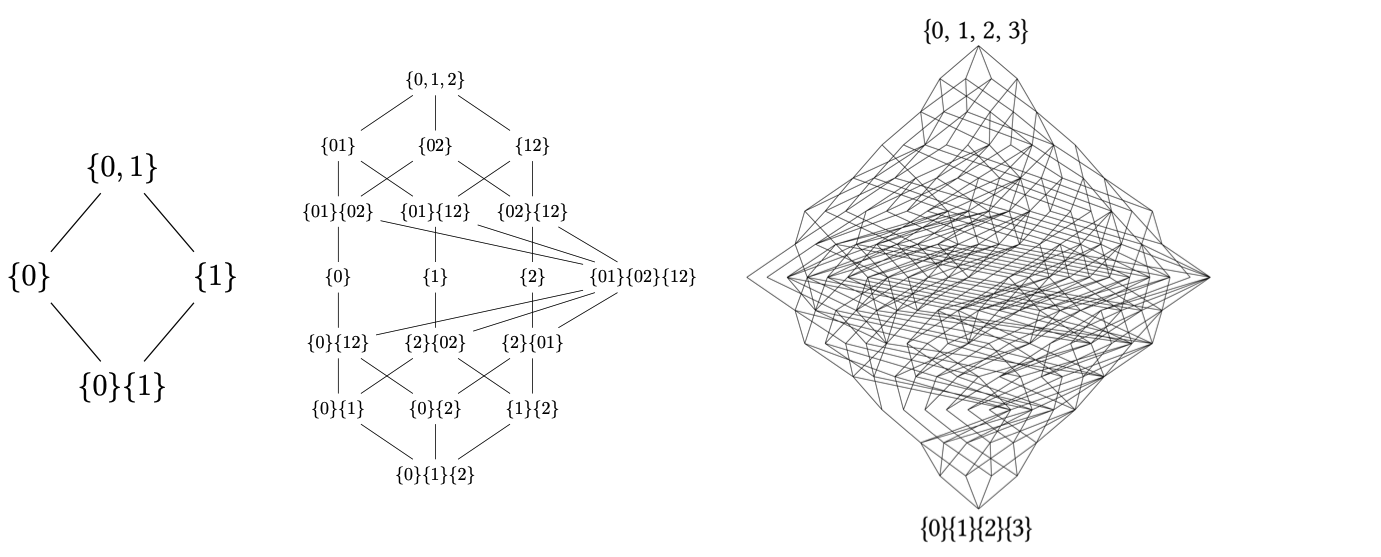

Here’s a picture of the power set mereology on systems with 2, 3, or 4 variables (which I’ve labelled simply as $0$, $1$, $2$, and $3$):

Each has the full system at the top (as any mereology should), the empty set at the bottom, and in between all the singletons, pairs, triplets, and so on. All three also clearly have ‘levels’ or ‘orders’ corresponding to horizontal slices.

This means that we can now ‘decompose’ the quantity $Q(S)$ over a mereology on $S$ as follows

\[Q(S) = \sum_{p \subseteq S} q(p)\]This now reads: $Q(S)$ is built from contributions from all the parts of $S$, including all possible combinations of them. Perhaps you are not yet convinced that we have gained anything by doing this. We have simply rewritten the decomposition of $Q$ in a more complicated form. However, mereologies have some special properties which allows us to do something pretty cool.

Möbius inversion

Let’s leave the mereology unspecified for now, and just say there is some mereology $(\mathcal{D}(S), \leq)$ on $S$. The decomposition of $Q(S)$ can be written as:

\[Q(S) = \sum_{p \leq S} q(p)\]By definition, every element of $\mathcal{D}(S)$ is a part of $S$. This means that if the full system $S$ has the property $Q(S)$, then any part $p$ might have the property $Q(p)$. Note that $Q(p)$ is not the same as $q(p)$—the former is a property of the part $p$, while the latter is the contribution of $p$ to the property of the whole system. Now it might make sense to say that the decomposition is valid for all parts:

\[Q(p) = \sum_{r \leq p} q(r)\]This means that we have a decomposition of $Q$ on every part. If there is a total of $N$ parts in the mereology, then this leads to $N$ equations (one decomposition of $Q$ per part), with $N$ unknowns (the contribution $q$ of each part). This is a system of equations that could in theory be solved, but for large mereologies this can be impractical. Since a mereology is a very special thing with a lot of structure, solving the equations is actually much simpler! The solution is given by the Möbius inversion formula:

\[Q(S) = \sum_{p \leq S} q(p) \quad \iff \quad q(S) = \sum_{p \leq S} \mu(p, S)Q(p)\]This says that whenever you have a sum over a mereology, you can actually invert this sum (‘solve the system of equations’). This gives you an expression for all the microscopic contributions $q(p)$, that are usually not directly observable, in terms of the observable properties of the parts $Q(r)$. $Q$ is a sum of $q$’s, but the $q$’s are themselves a sum of $Q$’s, weighed by a weird number called $\mu(p, S)$. This number is called the Möbius function of the mereology.

The precise definition of $\mu$ is not so important5. The only important thing is that it allows you to invert sums on a mereology, and that it is fully specified by the ‘shape’ of the mereology. Only the relationships between the parts matter—not what the parts actually are. For example, the power set mereology $(\mathcal{P}(S), \subseteq)$ that we saw before always has the same shape, no matter what kind of system $S$ is. This means that the Möbius function is always the same for the power set mereology. It is given by

\[\mu(p, S) = (-1)^{|S| - |p|}\]In other words: if you decompose $Q(S)$ over the power set mereology, then the microscopic $q(p)$ given by an alternating sum over $Q(p)$’s:

\[q(S) = \sum_{p \subseteq S} (-1)^{|S| - |p|}Q(p)\]Where $\mid S\mid - \mid p\mid$ refers to the difference in the number of elements in $S$ and $p$. Let’s look at two examples of this in practice.

Example 1: Consider a system of two genes $g_1$, and $g_2$. Let us decompose a person’s height $H$ over the power set mereology of these genes:

\[H(g_1, g_2) = \sum_{p \subseteq (g_1, g_2)} h(p) = {\color{grey}{h(\emptyset})} + {\color{YellowGreen}{h(g_1)}} + {\color{skyblue}{h(g_2)}} + {\color{Tan}{h(g_1, g_2)}}\]This says: the height of the person with both genes is given by some contribution $h(\emptyset)$ that forms the ‘baseline’ height, plus the contributions of each gene individually, plus the interaction of the pair of genes. Matching the colour scheme above, we can draw this as:

To infer the contribution of an individual gene, we apply the Möbius inversion formula:

\[h(g_1) = (-1)^{|g_1| - |g_1|}H(g_1) + (-1)^{|\emptyset| - |g_1|}H(\emptyset)\\ = H(g_1)- H(\emptyset)\]That is, the effect $h(g_1)$ of an individual gene is the difference between a person with that gene and a person without it. This makes sense! In fact, it makes so much sense that it is not very interesting. More interesting is the interaction term. A similar Möbius inversion yields:

\[h(g_1, g_2) = H(g_1, g_2) - H(g_1) - H(g_2) + H(\emptyset)\]which can be drawn as:

This is actually a well-known quantity in genetics, where it is known as an epistatic effect between the genes.

Example 2 In physics and information theory, one often quantifies the amount of information in a system by the entropy. The precise definition is not important for now, but let’s denote the entropy carried by two variables $(X, Y)$ by $H(X, Y)$. One could imagine that the total entropy is composed of contributions from the individual variables, and a contribution that is only carried by the pair. This amounts to a power set mereology:

\[H(X, Y) = I(X) + I(Y) + I(X, Y)\]We have omitted the empty set this time, since an empty set of variables carries no information. A Möbius inversion shows that

\[I(X, Y) = H(X, Y) - H(X) - H(Y)\]This is a quantity known as the mutual information between $X$ and $Y$, and represents one of the most fundamental concepts in information theory. While there are other ways to derive it, this shows that it is the unique way to decompose the entropy over subsets of variables.

Beyond power sets

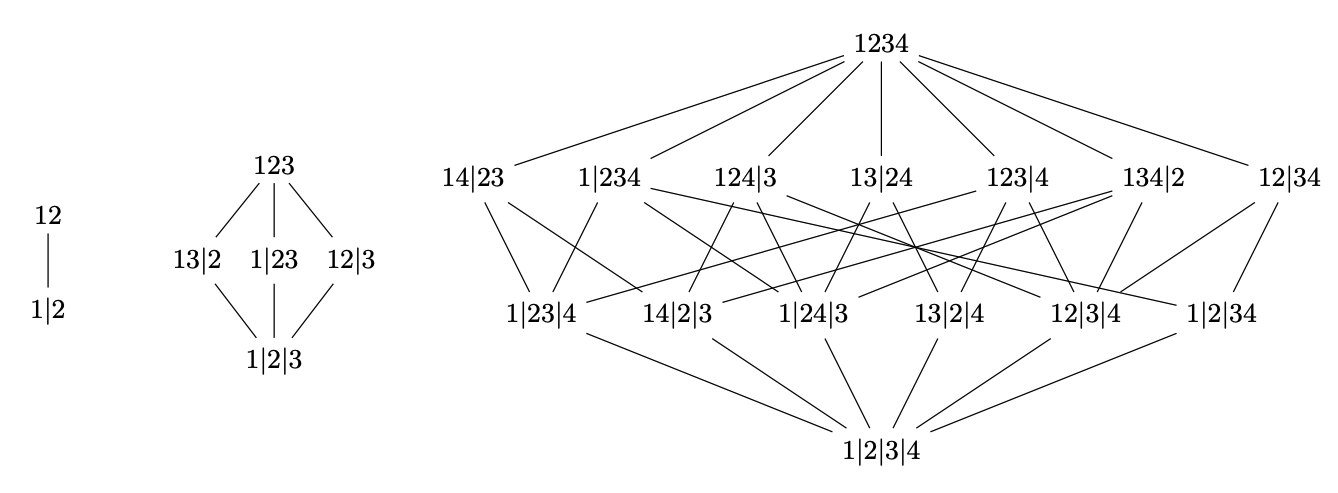

Both examples above use the power set mereology, which is especially simple6. In the paper, I find that Möbius inversions on different mereologies reproduce different quantities that are all well-known in certain fields of science. One alternative but common mereology is the ‘partition’ mereology, where a set is not divided into subsets, but into ‘partitions’—different ways to cut up a system. Here’s what that looks like for two, three, and four variables:

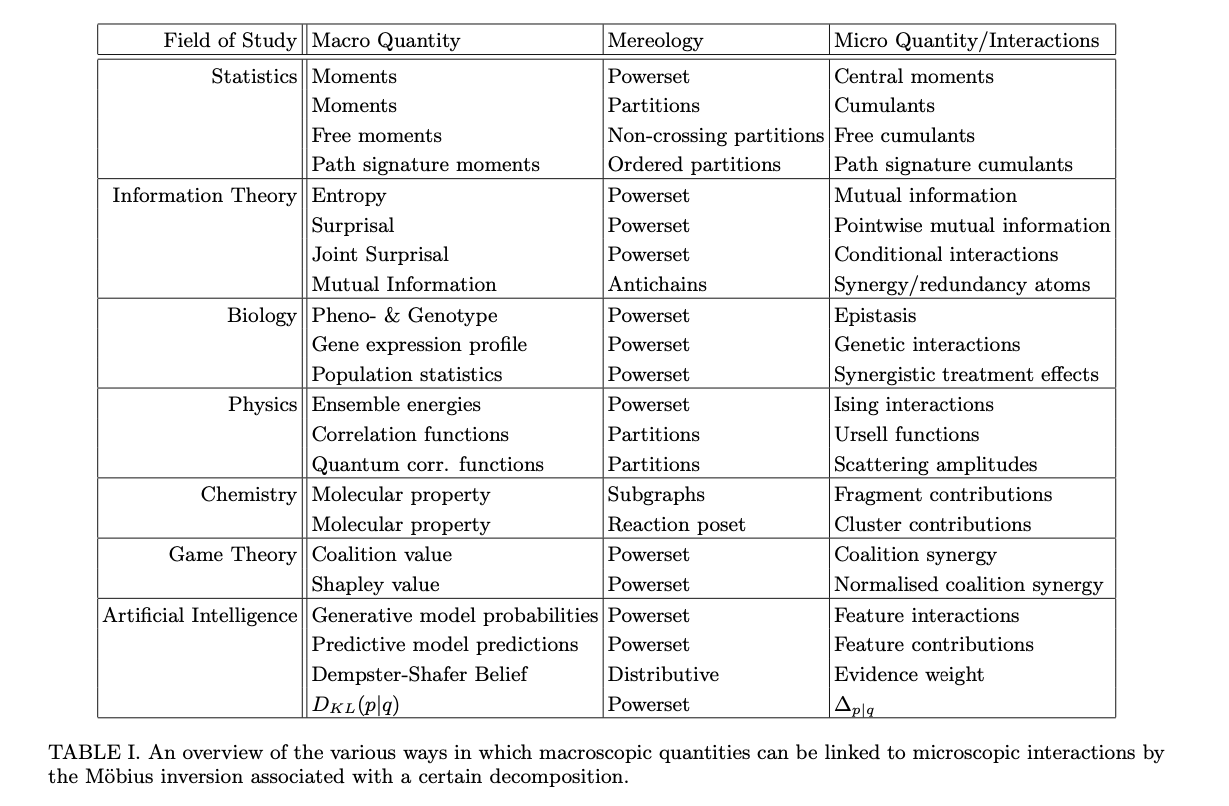

Table 1 from the paper gives an overview of how different mereologies are associated to different quantities:

To summarise: Most of the quantities above were the result of people thinking very hard about what the right definition of the microscopic ‘interaction’ terms are. However, instead of thinking hard about equations, you can instead invest this mental energy into thinking about appropriate mereologies. Once you have fixed the mereology, there is a unique microscopic description that is compatible with it. Not only that, the mereology shows you exactly what is meant by ‘higher-order’, namely, some terms are higher with respect to the partial ordering. This resonates strongly with Plato’s call to ‘carve Nature at its joints’—a good description of Nature depends on a good choice of parts. If you choose a natural mereology, then the higher-order interactions that derive from it inherit the justification.

Real-world applications

In the paper I use this approach7 to derive new notions of ‘higher-order’ interactions that can be used in machine learning (I derive a novel decomposition of the so-called KL-divergence). Another exciting application is ‘coarse-graining’. Physicists love studying what happens when you ‘coarse-grain’ a system—how does the physics change if you squint or look from far away? In essence, a coarse-graining is simply a change in mereology—a coarser description is one with fewer or larger parts. Describing coarse-grainings at the level of mereologies gives an entirely new way to think about this process. In one of the final sections of the paper I show that coarse-grainings correspond to special kinds of transformations of mereologies called Galois connections, and use this to derive well-known coarse-grained quantities (the ‘renormalised’ Ising couplings).

To apply the framework, you have to know the Möbius function $\mu$ of the mereology you are interested in. For one famous mereology—the so-called redundancy mereology—the Möbius function was not known. It is a particularly complex mereology and includes many8 parts:

However, in a recent collaboration with Pedro Mediano at Imperial College London, and Fernando Rosas at Sussex, we were able to calculate the Möbius function for this mereology, and therefore calculate new kinds of higher-order interactions (see the paper here). I’m now exploring what else can be done with this approach, and recently found a new way to decompose causal effects, as outlined here.

In short: there is lots to do. Stay tuned for more.

-

Thanks to Twitter/X user @prathyvsh for urging me to write this, and creating the figures of Brunnian links and visual algebra. They make really great visualisations of algebraic structures ↩

-

Mereology is the λόγος (logos: explanation/consideration) of a μέρος (meros: part). The meros root more famously appears in words like polymer (literally: manyparts). ↩

-

Mathematicians might notice how this is somewhat similar to the definition of a topology. The two are indeed related, but not the same. A topology on a finite set is necessarily a mereology, but not all mereologies are topologies, and topologies do not have to be finite. ↩

-

It’s interesting to ask: Why are beyond-pairwise interactions not common? I think it’s at least part caused by a lack of imagination. We can picture things interacting as a graph, where points represent parts, and lines represent interactions between parts. But lines always connect two points, not three or more, so we cannot really picture what higher-order interactions look like. This is a limitation of our imagination, not of Nature. However, pairwise descriptions have been very successful, and some people have argued that this is the way Nature works. Observing higher-order interactions from data is also harder than pairwise interactions, so perhaps it is simply a reflection of the fact that data sets have historically been small. This would also explain why higher-order interactions are becoming more en vogue now that data sets are getting bigger. ↩

-

The Möbius function is usually recursively defined over a partial order, but there is a very nice expression due to Phillip Hall: Given an interval $[x, y]$ on the partial order $P$, let $c_i$ be the number of chains in $P$ from $x$ to $y$ of length $i$. Then the Möbius function on $P$ is given by $\mu(x, y) = -c_1 + c_2 - c_3 + \ldots$. ↩

-

The Möbius inversion formula over the power set mereology is more famously known as the inclusion-exclusion principle. ↩

-

I’m still looking for a good name for this approach/framework. Möreology? If you have any suggestions—please let me know! ↩

-

In fact, the number of parts in this mereology for 9 variables was calculated for the first time in 2023, and for more than 9 variables is still unknown. ↩

physics biology cybernetics causality game-theory maths philosophy machine-learning information-theory